Getting Started with GSoC 2025 - Building a Routing Engine for PySAL

Hey there, I’m Dylan, welcome to my blog! I’m a doctoral student at San Diego State University, and I’ll be making regular posts throughout the summer as I work on my 2025 Google Summer of Code (GSoC) project. The goal of my project is to build a generalized routing engine for the spopt package in pysal. Most of my posts will cover the project itself: tracking my progress, describing my tools and workflows, and (hopefully) providing helpful information for other amateur developers interested in contributing to open-source software.

In this first post, I’ll briefly describe the project and my development environment.

When explaining this project in conversation, I’ve found myself saying: it’s a way to specify routing distances (including the actual routes) for optimization problems using user-provided data. For example, a user might need to model deliveries from a depot to customers via a road network. These kinds of problems are foundational in logistics operations and research.

A great example is the Guinness delivery problem, created by Dr. Levi Wolf, one of my mentors. Key parameters for such problems include the quantity of product to deliver, the number of available vehicles, customer destinations and demand, and delivery time windows. There are many possible routes through a city, but some will be faster or more efficient than others. The “best” route is what we aim to compute. These problems fall under a class called Vehicle Routing Problems (VRP).

The existing codebase already includes a solver for these problems, but my work this summer focuses on building an engine to fetch and format the appropriate road network data.

Development Environment

The first step was onboarding, which meant setting up a development environment.

As a student researcher at the Center for Open Geographic Science, I’m fortunate to have access to a powerful research server, way more powerful than my laptop. But editing code and writing prose directly on the server feels clunky compared to my finely-tuned Emacs setup.

To get the best of both worlds, I SSH from my local machine into the remote server, start a Jupyter Lab instance there, and run code remotely. I edit code and take notes locally in Emacs. I git push my changes to my fork and branch on GitHub, then git pull them into the Jupyter environment on the server.

This might seem clunky since I can’t directly edit and run code in one place. But there are advantages:

- I get the full power of Emacs — I’ve spent years refining my keybindings and

elispsetup to move smoothly between tasks and workflows. - I use

magitfor Git/GitHub — It makes committing and pushing code convenient and fluid, far better (to me) than the command line. - I’m forced to push often — This results in a richer commit history.

- I can run heavy tasks remotely — Optimization and network analysis require horsepower. The research server is essential here.

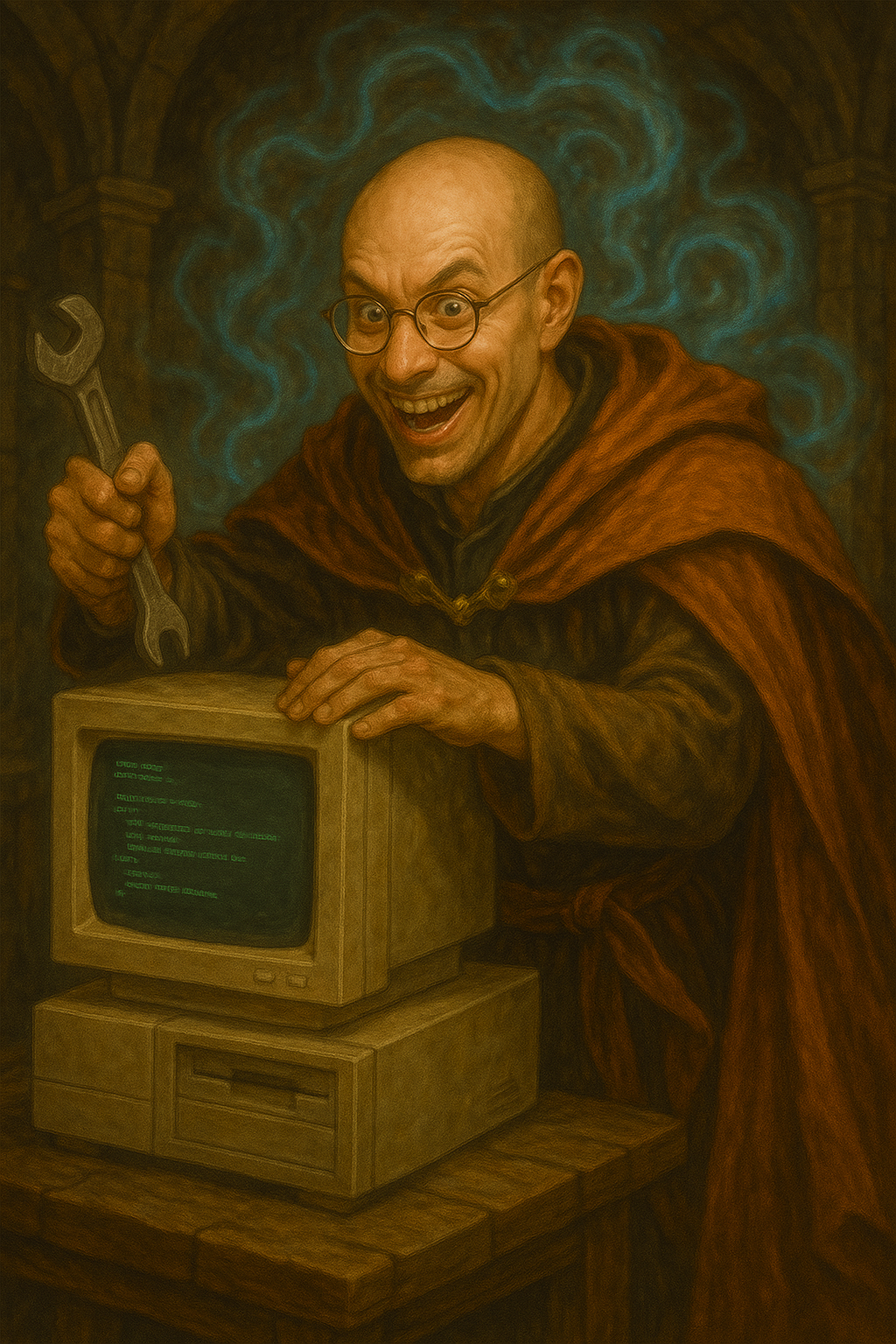

That said, “tunnel coding” isn’t perfect. I often need to tweak my PATH settings to get tools recognized. I’m not formally trained in computer science, everything I know is DIY. Growing up around computers in the ’90s helped develop solid intuition, but system config (like PATH stuff) is still a weak spot. Years of filesharing and keygen hacking have given me something greater than knowledge:

First Steps

With my setup ready, I created a new environment using mamba, cloned the draft pull request for the project, and made sure the new module was installed.

Then I thought: Let’s just grab this thing and see how far I can get running it as-is.

Naturally, I hit a traceback within three lines—turns out the interpreter was trying to set an index on a network identifier I didn’t have. The solver is supposed to recognize that there is no network provided and solve using euclidean (or as the crow flies) distance. Since I’ve spent most of the day getting set up here, I will take importing the pull request as a successful work day. Next time, I will describe how the solver can work without a road network, as well as describe how we’re approaching a generalized implementation of a routing engine.